Are we the only sane ones left?

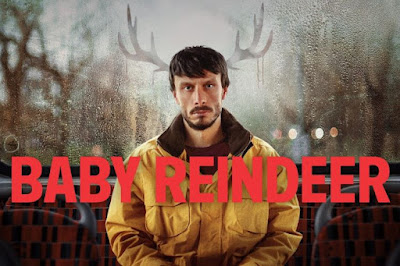

It's a story of two lives falling apart, dramatically, in their different but terrifyingly intertwined ways, with a deft sub theme that leaves the viewer asking questions about who needs who most in this deepening hell. Though each character is well written and eye catching (the performance of Jessica Gunning as Martha, the stalker, is a tour de force), one character, and one story, for me also stood out in a drama which dimensionalises its protagonists and tackles themes in ways viewers may not have previously seen. This is Teri, a trans woman who is written with dignity and honesty and based on a real person with whom, Gadd says, he fell in love and who kept him grounded when everything was unravelling. Gadd's character, 'Donny', meets Teri, who works as a therapist, on a trans dating site, as part of a journey he is taking to understand his sexuality and to make sense of a traumatic and buried past. Teri (played by Nava Mau) is beautiful, smart, articulate and strong, and as her relationship with Donny deepens, her unintended contact with her boyfriend's increasingly psychotic stalker grows.

Most of the media coverage has been about the cisgender roles in this story, and especially the commentary the drama makes on mental illness and abuse. IMDb, typically, features hundreds of glowing reviews, moreorless erasing the role of Teri entirely. Broadcast and legacy media coverage has felt the same. There are probably good reasons for this and bad ones. On the former side, the drama is principally a highly nuanced one about stalking, abuse and mental health; themes which remain unaddressed in British society, with support for sufferers and victims inadequate and contextualised by brutal rhetoric from a right wing government with its obsessions about sick notes and the economically unproductive in our society. But there's a more depressing explanation too - Teri's role in the plot is as the viewer's eyes. She says the things we are thinking as we witness the disintegration of the two main characters. She is the one to whom we are supposed to relate. Whoever heard of such a thing - a trans woman being relatable? Perhaps the media has felt uneasy about making that point by foregrounding her role, and its meaning, in much coverage.A whiff of Britain in 2024 of course. Whilst reviewers might claim plausible deniability (Teri is a supporting character, albeit the major one, not a lead), a trans character taking this role in the drama - something that requires no explanation if you watch the series and get to know her - might just be regarded as bit too alien for a reviewer to explain to a cisgender audience (or even for the reviewer to tackle as it brings up questions for them about their own views?). Plus ca change - Teri has been mostly erased from commentary (there are some exceptions here and, briefly, here and a couple of women's weekly magazines have run brief features). She is the absolute reverse of the prevalent media narrative and this sympathetic, honest, portrayal, presenting Teri as profoundly normal in a profoundly abnormal situation, doesn't chime in any way with a popular narrative of fear around trans women. It would be hard to build a case to discriminate against someone like her (though some would still try); that such a character appears (based on a real person) and is handled so well by Nava Mau feel all the more subversive in our current culture.

Mexican, mixed-race, trans actress Mau clearly took it very seriously. “I could tell Richard [Gadd] really loved her, whoever inspired this character” she said. “I knew that it was based on real life and it seemed really important to show people that trans women exist in real life and in relationships with real people. I could see Richard’s heart in the writing and I hope that people will see it too. I felt a great sense of responsibility…”

Teri’s character has stuck with me. As a trans woman, I see much to recognise. Some of it is to do with the nature of being a trans woman, fighting for acceptance every second of every day, semi-faking a convincing (I hope) picture of confidence in the world, while masking an anxiety and a hyper-vigilance that is sometimes just a few notches below fear. Teri is a successful professional – a therapist – nicely dressed and clearly doing ok. I really wanted to be her.Yet, like all trans women she too must deal with the marginalisation that society imposes on her. If she is looking for love with a man, she must deal with the deep self-hate many feel about being attracted to trans women. She must rely on ‘specialist’ trans dating sites, where guys seek out trans women specifically. These sites can produce successful relationships, if the cis man is able to do some work to face down their introjected shame, but they are heavily populated with time wasters who feign interest from the safety of their laptops, fetishising and objectifying the women they find, and then often standing them up should they (have to seeming courage to) arrange a date.

I know this from many stories from others, and it has happened to me, twice, both times leaving me humiliated in a restaurant alone (before I learned, soon after my transition, that this was how I would have to expect to be treated). Another, very present, type of guy is the chaser; the man who will meet a trans woman but only secretly, often under a false name, in a discrete or remote location, or perhaps a secluded trans or gay venue. Terrified of anyone ever knowing that he is attracted to such a person, he will tell no-one (he may well be married) and keep his relationship secret, leading his trans girlfriend on with excuses or lies until, eventually she realises that he will never be free of his shame. Donny is seen behaving this way to Teri in early episodes, and even as the situation worsens with his stalker, and the latter intrudes violently into their relationship, his crucifying self hatred remains. A sub-variant of this type of man sexualises trans women, picks them up in bars, has sex with them, then discards them the next day, sometimes with disgust or having expressed their self-revulsion with their fists; a behaviour that, again, has happened to people I know of.

Though it is possible to find a relationship on a more 'mainstream', cis-dominated forum, and some have, the trans woman – no matter what she says about herself, or how she appears, usually faces a grim choice. She may share something of her gender history, even (if she feels that she must), her surgical or medical history (something that few cisgender women are likely to ever feel the need to do - its hardly the come-on that you'd pick first for your dating profile - and why should they?) and then spend the next few weeks watching her profile get no hits at all, her empty inbox gathering dust. Or she can say nothing about her past, judging that it’s better for her to share her story at a time when her date has got to know her a little and developed some sort of bond. I have tried both approaches. Lucky enough to have what we call ‘passing privilege’, years ago, I met a few guys without sharing my life story beforehand. A couple of them went no further than a first date, they were dull as hell and I pulled the plug before any dilemmas arose. One I saw for a perhaps six weeks and when I did share my 'news' he was, to his huge credit, sweet and kind. Another I spent a great night with – we seemed to have real chemistry, bonding and swapping shared interests all night. I felt hopeful - he kissed me at the end of the evening and I’m sure he wanted more. But when I heard nothing from him after our evening and I reached out a few days later, I received insults and rage. He had, I realised, doxed me, likely discovering reference to a LGBTQ+ conference at which I had spoken a few years before. He made cruel jokes about me.

I cried in the toilets at work that day, though, in fact, I was lucky. I might have been in line for worse, especially as he’d already kissed me (luckily, for me, I’d guided him away from pressing further). If you are a trans woman, you’ll know what I am about to refer to; the abuse or even violence that can follow when your date ‘learns your secret’. His shame can even get you killed – it has happened - and in both the United States and the United Kingdom the defence of ‘trans panic’ has been used by defence lawyers to try and excuse this behaviour in the subsequent trial (this asserts that an individual can be so disgusted on discovering that a partner is transgender that their violence is somehow excusable, explicitly valuing a trans life as less than a cisgender one). Though, effectively, legally dead in the UK, the trans panic defence is still available in many US states and in the current climate in parts of the country there, might be due a reappearance.

Watching Teri in the show, I knew that she knew all this, and it is touched on in the script. I know, that the actress knows it too, because she and I, as trans women, both cannot not know it (Mau, who is also active in LGBTQI+ rights work, made a short film (Waking Hour) which succinctly captures the choices trans women often have to make between being rejected and othered, or treated as little more than carnal, objectified objects). This is why Mau can inhabit the role fully and, in a way that a cisgender woman never could. Both character and actress have had to navigate such fears. I can sense the wounds inside. For me, for many trans women, perhaps, there's a bodily recognition of them.

Despite all this, Teri is living her best life in Baby Reindeer. It’s a story that was written some years ago now, located in the years 2015-2017. It’s not one in which a degenerating public climate, spiralling hate crime, a putrid, corrupt, transphobic and morally septic British government appears. It was refreshing to see that a life without these concerns, albeit just within the dramatic frame of a seven part Netflix series, could even exist and it was refreshing to see a trans woman simply getting on with her life. These are experiences that I find harder to remember in my own life all the time now especially when I see a newspaper website or read anything coming from government politicians. I wondered, in fact, how Teri might be doing now – is she still able to keep her therapy practice going? Has she fled back to the US (the character, we are led to believe, is American), and if so, let's pray its not to Texas, or Alabama, or Oklahoma, or Florida or any number of states where the situation for people like her is deteriorating fast (I will, next year, be be emigrating to Ireland to get way from the endless British narrative of prejudice and bigotry. I feel forced out of the country of my birth - Ireland is no utopia, with a small but violent hard right, but it's not like Britain).

I admired Teri for making it work, for being the rock in the drama and a lone voice of reason as those around her fragmented. I tried to learn some lessons from her – but it’s become so hard to do that in this country now.

I hoped, somehow, that she was still in her North London flat, having found someone to love her and to keep her safe.

****

* This, of course, has not stopped The Worst People On The Internet from going into action to try and find the real identities of various characters in it, and questions are being asked about how well he did this. He, and Netflix, might have perhaps done more.

Do note that Baby Reindeer contains some very difficult scenes, including of sexual abuse. Episode Four is particularly challenging. Each episode contains warnings - take them seriously if you feel that you might be vulnerable.

.svg.png)

Comments

Post a Comment

Leave a comment here. Comments are moderated. Spam or abuse isn't going to get through.